I. Unconditional war

On January 8, 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared an “unconditional war on poverty in America.”

The effort spawned the creation of Medicare, Medicaid, food stamps, the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, and the Elementary and Secondary Education Act. (The ESEA has been renewed every 5 years since; when renewed in 2001, it went by the moniker “No Child Left Behind”.)

1965 also saw the launch of the Head Start Program, designed to provide early childhood education to low income children while involving the parents.

The program was designed to promote the growth and development of parents and their children. The Planning Committee for Head Start felt that children would benefit from their parents’ direct involvement in the program. They agreed that the best way for parents to learn about child development was by participating with their children in the daily activities of the program.

— Sarah Merrill

At the time, parental involvement was controversial:

Although parent involvement was written into law in 1967, their role in governance was spelled out for the first time in 1970 through Part B in the Head Start Policy Manual. This policy was also known as 70.2. Policy 70.2 defined the responsibilities of Policy Councils at the program, delegate, and agency levels. At that time, many Head Start grantees—especially those in public school settings—called Washington, DC and threatened to leave Head Start because 70.2 gave so much authority to parents.

— Sarah Merrill

This point is important for what’s to come.

II. 352,000

In 1967, Congress authorized funds to expand Head Start under a program called Follow Through.

Congress authorized Follow Through in 1967 under an amendment to the Economic Opportunity Act to provide comprehensive health, social, and educational services for poor children in primary grades who had experienced Head Start or an equivalent preschool program. The enabling legislation anticipated a large-scale service program, but appropriations did not match this vision. Accordingly, soon after its creation, Follow Through became a socio-educational experiment, employing educational innovators to act as sponsors of their own intervention programs in different school districts throughout the United States. This concept of different educational improvement models being tried in various situations was called “planned variation.”

— Interim Evaluation of the National Follow Through Program, page 22

In other words, Congress approved a service program which had to be cut down due to lack of funds to an experimental program.

Various sponsors — 22 in all — picked particular models that would be used for a K-3 curriculum (although it should be noted that due to the social service origin not every sponsor had a curriculum right away — more on that later). Four cohorts (the first group entering in fall 1969, the last fall 1972) went through the program before it was phased out, the last being very scaled down:

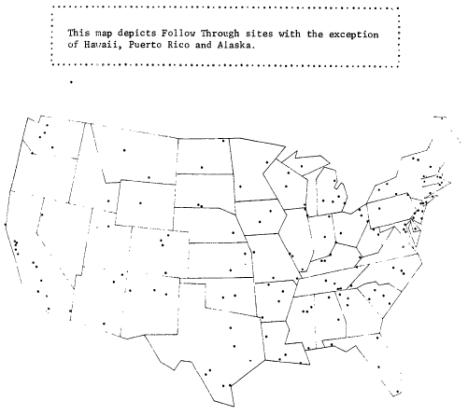

The sponsors had classrooms spread throughout the entire country implementing curriculum as they saw fit.

[Source.]

Note that this was not a case of them putting in their colleagues; teachers were chosen from sites and given their curriculum via trainers or handbooks. Other teachers taught “comparison groups” not using the interventions that were chosen to be as similar as possible to the experimental groups. The idea was to see if students using the sponsor’s curriculum would outperform the comparison groups.

Teachers were not always happy being forced to participate:

New Follow Through teachers sometimes resisted changing their teaching strategies to fit the Follow Through models, and they found support for their resistance among others who felt as powerless and as buffeted as they.

— Follow Through Program 1975-1976, page 31

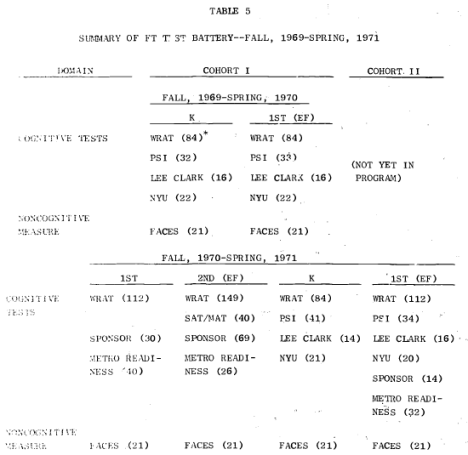

A wide swath of measures was chosen to assess quality.

[Source.]

Notice the number that says “Sponsor” — those are questions submitted by the sponsors, knowing the possibility of a mismatch between the curriculum learned and the curriculum tested.

Not all of the data above was used in the final data analysis. By the end of the experiment the main academic measure was the Metropolitan Achievement Test Form F Fourth Edition. Note the only minor use of the MAT in the chart above representing the early years (noted by SAT/MAT — MAT and Stanford word problems were mixed together). Sponsor questions, for instance, dropped by the wayside.

In 1976 the program ended and the program as a whole was analyzed — 352,000 Follow through and comparison children — resulting in a report from 1977 called Education as Experimentation: A Planned Variation Model.

The best summary of the results comes from three charts, which I present directly from the book itself. The dots are the averages, the bars represent maximums and minimums:

“Basic skills” represents straightforward reading and arithmetic, “cognitive skills” represent complex problem solving, and “affective skills” dealing with feelings and emotional areas.

The report makes some attempt to combine the data, but the different programs are so wildly dissimilar I don’t see any validity to the attempt. I’d first like to focus on five of them: SEDL, Parent Education, Mathemagenic Activities, Direct Instruction, and Behavior Analysis.

III. SEDL

The Southwest Educational Development Laboratory (SEDL) model is a bilingual approach first developed for classrooms in which 75 percent of the pupils are Spanish-speaking, but it can be adapted by local school staffs for other population mixes. In all cases the model emphasizes language as the main tool for dealing with environment, expressing feelings, and acquiring skills, including nonlinguistic skills. Pride in cultural background, facility and literacy in both the native language and English, and a high frequency of “success” experiences are all central objectives.

— Follow Through Program Sponsors, page 31

The SEDL is a good example to show how difficult it is to compare the sponsors; in this case rather than forming a complete curriculum, the emphasis of SEDL is on helping Spanish speakers with a sensitive and multicultural approach. The goals were not to gain basic skills in arithmetic, oral skills are emphasized over written, and based on the target sample there was a higher difficulty set on improving reading.

Given these factors, the result (smaller effect on basic skills, larger effect on cognitive and affective development) seems to be not surprising at all.

IV. Parent Education

This sponsor perhaps makes it clearest that Follow Through started as a social service program, not an education program.

A fundamental principle of the BOPTA model is that parents and school personnel can, and want to, increase their ability to help their children learn. Also, parents and school personnel together can be more effective than either can alone. The sponsor’s goal is to assist both school and home to develop better child helping skills and ways to implement these skills cooperatively and systematically. These child helping skills are derived from careful study of child development, learning, and instructional theory, research, and practice. The, approach is systematically eclectic and features both diagnostic sequential instruction and child-initiated discovery learning.

— Follow Through Program Sponsors, page 37

The results from the data for this program were roughly around average; basic skills did slightly better than cognitive skills. However, the idea of including home visits training makes a much different set of variables than just training the teacher.

Related but even more dissimilar was the Home School Partnership:

A parent aide program, an adult education program, and a cultural and extra-curricular program are the principal elements of this model. The model aims to change early childhood education by changing parent, teacher, administrator, and child attitudes toward their roles in the education process. It is believed this can be done by motivating the home and school to work as equal partners in creating an environment that supports and encourages learning.

— Follow Through Program Sponsors, page 25

This is a program that had no educational component at all — it was comparing parent intervention versus no parent intervention, which led to confusion:

The instructional component of this program is in disarray. Since there is no in-class instructional model, teachers are on their own. Some are good, but in too many classes bored children and punitive teachers were observed.

— Follow Through Program 1975-1976, page 66

Note that in both cases, however, as mentioned earlier: the idea of home parental involvement was innovative and controversial enough on its own it created a burden the other projects did not have. (To be fair, teachers as in-class aides occur in the other programs.)

V. Mathemagenic Activities

This sponsor ran what most people would consider closest to a modern “discovery” curriculum.

The MAP model emphasizes a scientific approach to learning based on teaching the child to make a coherent interpretation of reality. It adheres to the Piagetian perspective that cognitive and affective development are products of interactions between the child and the environment. It is not sufficient that the child merely copy his environment; he must be allowed to make his own interpretations in terms of his own level of development.

An activity-based curriculum is essential to this model since it postulates active manipulation, and interaction with the environment as the basis for learning. Individual and group tasks are structured to allow each child to involve himself in them at physical and social as well as intellectual levels of his being. Concrete materials are presented in a manner that permits him to experiment and discover problem solutions in a variety of ways.

…

The classroom is arranged to allow several groups of children to be engaged simultaneously in similar or different activities. Teachers’ manuals including both recommended teaching procedure and detailed lesson plans for eight curriculum areas (K-3) are provided in the model. Learning materials also include educational games children can use without supervision in small groups or by themselves. Art, music, and physical education are considered mathemagenic activities of equal importance to language, mathematics, science, and social studies.

— Follow Through Program Sponsors, page 33

MAP did the best of all the sponsors at cognitive skills and merely over baseline on basic skills.

The term “mathemagenic” was 60s/70s term that seems not to be in use any more. A little more detail from here about the word:

In the mid-1960’s, Rothkopf (1965, 1966), investigating the effects of questions placed into text passages, coined the term mathemagenic, meaning “to give birth to learning.” His intention was to highlight the fact that it is something that learners do in processing (thinking about) learning material that causes learning and long-term retention of the learning material.

When learners are faced with learning materials, their attention to that learning material deteriorates with time. However, as Rothkopf (1982) illustrated, when the learning material is interspersed with questions on the material (even without answers), learners can maintain their attention at a relatively high level for long periods of time. The interspersed questions prompt learners to process the material in a manner that is more likely to give birth to learning.

There’s probably going to be interest in this sponsor due to the obscurity and actual performance, but I don’t have a lot of specific details other than what I’ve quoted above because. It’s likely the teacher manual that was used during Follow Through is buried in a university library somewhere.

VI. Direct Instruction

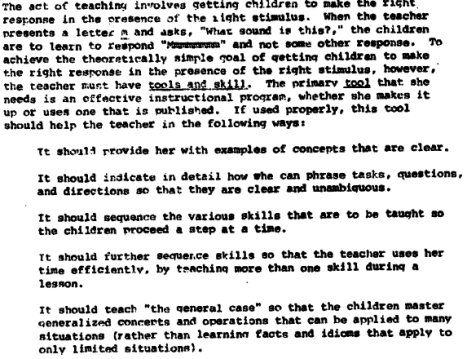

This one’s worth a bigger quote:

[Source; quotes below from the same source or here.]

This one’s often considered “the winner”, with positive outcomes on all three tests (although they did not get the top score on cognitive skills, at least it improved over baseline).

What I find perhaps most interesting is that the model does not resemble what many think of as direct instruction today.

Desired behaviors are systematically reinforced by praise and pleasurable activities, and unproductive or antisocial behavior is ignored.

The “carrot rather than stick” approach reads like what currently labeled “progressive”. The extremely consistent control is currently labeled “conservative”.

In the classroom there are three adults for every 25 to 30 children: a regular teacher and two full-time aides recruited from the Follow Through parent community. Working very closely with a group of 5 or 6 pupils at a time, each teacher and aide employs the programmed materials in combination with frequent and persistent reinforcing responses, applying remedial measures where necessary and proceeding only when the success of each child with a given instructional unit is demonstrated.

The ratio here is not 1 teacher lecturing to 30 students. It is 1 to 5.

Emphasis is placed on learning the general case, i.e., developing intelligent behavior, rather than on rote behavior.

While the teacher explains first, the teacher is not giving mute examples. They are trying to make a coherent picture of mathematics.

Before presenting the remaining addition facts, the teacher shows how the facts fit together–that they are not an unrelated set of statements. Analogies teach that sets of numbers follow rules. Fact derivation is a method for figuring out an unknown fact working from a known fact. You don’t know what 2+5 equals, but you know that 2+2 equals 4; so you count.

2 + 2 = 4

2 + 3 = 5

2 + 4 = 6

2 + 5 = 7Then the children are taught a few facts each day so that the facts are memorized.

This is the “counting on” mentioned explicitly in (for example) Common Core and possibly the source of the most contention in all Common Core debates. This differs from those who self-identify with “direct instruction” but insist on rote-first.

Also of note: employees included

a continuous progress tester to reach 150 to 200 children whose job it is to test the children on a 6 week cycle in each core area.

Assessment happened quite frequently; it is not surprising, then, that students would do well on a standardized test compared with others when they were very used to the format.

VII. Behavior Analysis

The behavior analysis model is based on the experimental analysis of behavior, which uses a token exchange system to provide precise, positive reinforcement of desired behavior. The tokens provide an immediate reward to the child for successfully completing a learning task. He can later exchange these tokens for an activity he particularly values, such as playing with blocks or listening to stories. Initial emphasis in the behavioral analysis classroom is on developing social and classroom skills, followed by increasing emphasis on the core subjects of reading, mathematics, and handwriting. The goal is to achieve a standard but still flexible pattern of instruction and learning that is both rapid and pleasurable.

…

In the behavior analysis classroom, four adults work together as an instructional team. This includes a teacher who leads the team and assumes responsibility for the reading program, a full-time aide who concentrates on small group math instruction, and two project parent aides who attend to spelling, handwriting, and individual tutoring.

— Follow Through Program Sponsors, page 9

I bring up this model specifically because

a.) It often gets lumped with Direct Instruction (including in the original chart you’ll notice above), but links academic progress with play in a way generally not associated with direct instruction (the modern version would be the Preferred Activity Time of Fred Jones, but that’s linked more to classroom management than academic achievement).

b.) It didn’t do very well — second to last in cognitive achievement, barely above baseline on basic skills — but I’ve seen charts claiming it had high performance. This is even given it appears to have included assessment as relentlessly as Direct Instruction.

c.) It demonstrates (4 to a class!) how the model does not resemble a standard classroom. This is true for the models that involve a lot of teacher involvement, and in fact none of them seem comparable to a modern classroom (except perhaps Bank Street, which is a model that started in 1916 and is still in use; I’ll get to that model last).

Let’s add a giant grain of salt to the proceedings —

VIII. Data issues

There was some back-and-forth criticizing the statistical methods when Education as Experimentation: A Planned Variation Model was published in 1977. Quite a few papers were written 1978 and 1981 or so, and a good summary of the critiques are at this article which claims a.) models were combined that were inappropriate to combine (I agree with that, but I’m not even considering the combined data) b.) Questionable statistics were used (particularly getting fussy about reliance on analysis of covariance) and c.) the test favored particular specific learnings (so if a class was strong in, say, handwriting, that was not accounted for).

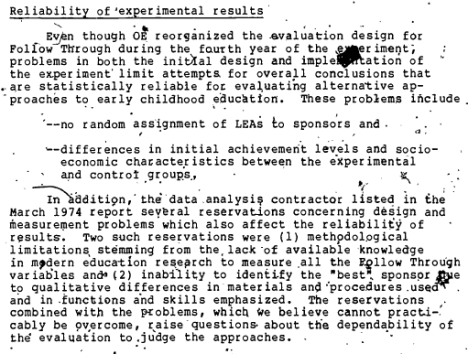

I think the harshest of data critique came before the 1977 report even came out. The Comptroller General of the U.S. made a report to Congress in October 1975 and was blistering:

The “data analysis contractor” mentioned presenting reservations are the same Abt Publications that came out with the 1977 report.

The report also mentions part of the reason why 22 sponsors are not given in the comparison graph:

Another result of most LEAs not being restricted in their choice of approaches is that some sponsors were associated with only a few projects. The evaluation design for cohort three–the one OE plans to rely most heavily on to determine model effectiveness–requires that a sponsor be working with at least five projects where adequate testing had been done to be compared with other sponsors.

Only 7 of the 22 sponsors met that requirement.

By the end, some sponsors were omitted from the 1977 report altogether. The contractor was also dubious about analysis of covariance:

In an effort to adjust for the initial differences, the data analysis contractor used a statistical technique known as the analysis of covariance … however, the contractor reported that the Follow Through data failed to meet some requirements believed necessary for this technique to be an effective adjustment device.

Additionally:

Further, no known statistical technique can fully compensate for initial differences on such items as pretest scores and socioeconomic characteristics. Accordingly, as OE states in its June 1974 summary, “the basis for determining the effects of various Follow Through models is not perfect.” Our review of the March 1974 report indicated that, for at least four sponsors, the adjustments were rather extensive. Included among the four is the only sponsor that produced significant differences on all four academic measures and the only two sponsors that produced any academic results significantly below their non-Follow-Through counterparts.

This issue was noted as early as 1973, calling out the High Scope, Direct Instruction, and the Behavior Analysis models specifically.

Substantial analysis problems were encountered with these project data due to non-equivalence of treatment and comparison groups.

— Interim Evaluation of the National Follow Through Program 1969-1971

(High Scope was one of the models on the “open framework” end of the scale; students experience objects rather than get taught lessons.)

The extreme data issues with Follow Through may be part of the reason why quasi-experiments are more popular now (taking some natural comparison between equivalent schools and adjusting for all the factors via statistics). When the National Mathematics Advisory Panel tried to locate randomized controlled studies, their report in 2008 only found 8 that matched their criteria, and most of those studies only lasted a few days (the longest lasted a few weeks).

IX. Conclusions

These days Follow Through is mostly brought up by those supporting direct instruction. While the Direct Instruction model did do well,

a.) The “Direct Instruction” does not resemble the direct instruction of today. The “I do” – “now you do” pattern is certainly there, but it occurs in small groups and with general ideas presented up front like counting on and algebraic identities. “General rather than rote” is an explicit goal of the curriculum. The original set up of a teacher only handling five students at a time with two aides is not a comparable environment to the modern classroom.

b.) The group that made the final report complained about the inadequacy of the data. They had misgivings about the very statistical method they used. The Comptroller of the United States in charge of auditing finances felt that the entire project was a disaster.

c.) Because the project was shifted from a social service project to an experimental project, not all the sponsors were able to handle a full educational program. At least one of the sponsors had no in-class curriculum at all and merely experimented with parental intervention. The University of Oregon frankly ran their program very efficiently and had no such issue; this lends to a comparison of perhaps administrative competence but not necessarily curricular outlook. For instance, the U of O’s interim report from 1973 noted that arithmetic skills were no better than average in the early cohorts, so adjusted their curriculum accordingly.

d.) While Direct Instruction did best in basic skills, on the cognitive measures the model that did best was a discovery-related. Based on descriptions of all the models Mathemagenic perhaps the closest to what a modern teacher thinks of as an inquiry curriculum.

e.) Testing was relentless enough in Direct Instruction they had an employee specifically dedicated to that task, while some models (like Bank Street) did no formal testing at all during the year.

Of the two other models noted in the report as being in the same type as Direct Instruction, Behavior Analysis did not do well academically at all and the Southwest Educational Development Laboratory emphasis on language and “pride in cultural background” strikes a very different attitude than the controlled environment of Direct Instruction’s behaviorism.

X. A Lament from Bank Street

Before leaving, let’s hear from one of the groups that did not perform so well, but was (according to reports) well managed: Bank Street.

In this model academic skills are acquired within a broad context of planned activities that provide appropriate ways of expressing and organizing children’s interests in the themes of home and school, and gradually extend these interests to the larger community. The classroom is organized into work areas fine; with stimulating materials that allow a wide variety of motor and sensory experiences, as well as opportunities for independent investigation in cognitive areas and for interpreting experience through creative media such as dramatic play, music, and art. Teachers and paraprofessionals working as a team surround the chidren with language that they learn as a useful, pleasurable tool. Math, too,is highly functional and pervades the curriculum. The focus is on tasks that are satisfying in terms of the child’s own goals and productive for his cognitive and affective development.

— Follow Through Program Sponsors, page 7

Bank Street is still around and has been for nearly 100 years. While their own performance tests came out positive, they did not do well on any of the measures from Abt’s 1977 report.

In 1981, one of the directors wrote:

The concepts of education we hold today are but variations of the fundamental questions that have been before is since the origins of consciousness. Socrates understood education as “discourse”, a guidepost in the search for wisdom. He valued inquiry and intuition. In contrast, Plato conceived of the State as the repository of wisdom and the overseer of all human affairs, including education. He was the first manager. As so has it always evolved: Dionysian or Apollonian, romanticism or classicism, humanism or behaviorism. All such concepts are aspects of one another. They contribute to evolutionary balance. They allow for alternative resolutions to the same dilemmas and they foster evolutionary change. Thus, a model is not a fixed reality immobilized in time. It is, as described above, a system, an opportunity to structure and investigate a particular modality, to be influenced by it and to change it by entering into its methods. The Bank Street model does not exist as a child-centered, humanistic, experientially-based approach standing clearly in opposition to teacher-centered, behaviorist modalities. These polarities serve more to define the perceived problem than they do to describe themselves.

— Follow Through: Illusion and Paradox in Educational Experimentation

Filed under: English, History, Mathematics, Politics, Statistics |

Hi Dan, thanks for this lovely compilation. I’d love to interact at length with you here about this, but have other tasks that make it difficult to dig particularly deep in the short term so I hope you’re not bothered by me coming and going and commenting in flurries followed by periods of silence. But after all, the interwebs are the home of asynchronous communication, n’est-ce pas?

Glad to see you got up to snuff pretty quickly — a couple of months ago when we first chatted you apparently had no familiarity yet with the largest educational study in history. Funny what they leave out of Education Graduate School nowadays.

I don’t have much to say initially (there’s a lot here that will take a more concerted effort — and that won’t stop me from blathering on anyway), but I’d like to take on an assumption you make here and in numerous places elsewhere that DI = lecturing, or perhaps ≈.

It does not, and certainly doesn’t in the context of interest to this discussion. We will get nowhere if you persist in mischaracterizing the position of those with whom you apparently disagree. Nobody is advocating lecturing as a primary form of instruction in K-8 math classrooms, which is what this discussion is about.

As you note, Engelmann’s DI is a particular manifestation of what some call direct instruction, and very unlike your (apparent) favourite straw-man version of the approach. Direct instruction is, simply put, conventional instruction in which the teacher directly conveys information to be learned to the student — this may be done with a wide variety of methods, only one of which is “lecturing”. There is a clear discussion of the usual terms of discourse and some specific manifestations of direct instruction in Anna Stokke’s CD Howe report (p. 5) — I suggest you review this. Note that at no point in her report does Stokke mention “lecturing” — it is irrelevant to the discussion.

You’re simplistic categories such as “rote-first” do not capture many, if any, advocates in this discussion. Rote is a word that simply means “by repetition” — it is a tool, no more, no less. Repetition follows initial learning (almost by definition), so it’s hard to grasp what might be meant by “rote-first”. Repetition is a key to automatization of skills and of embedding abstract information in long-term memory, and thus is an indispensable tool for learning. That rote is demagogued by educationists ignorant of its meaning, taking it to imply “without understanding” is no big surprise as repetitive exercises do not fit well with many discovery-focussed approaches to instruction. However, there is no sense in which repetition and understanding are antithetical aspects of learning. Indeed, I would argue that repetition is frequently necessary to properly embed understanding. In any case, they can — and often do — go very well together.

Our point is not that we want everyone to adopt Engelmann-style DI. I am not enamoured by DISTAR’s explicit reliance on the behaviouristic model. Currently available systems of instruction such as JUMP Math use a similar approach in which the feedback cycle is less rigid, less explicitly behaviouristic, and produces very similar results to Engelmann’s system in affective, skills and cognitive domains.

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/04/18/a-better-way-to-teach-math/?_r=0

I believe we have touched on JUMP in our previous discussion — so I won’t go back over it.

You have yourself looked at the PCAP Direct v Indirect instruction scale and done your best to run interference on its clear correlation of DI with math scores in that cross-Canadian assessment, which follows more-or-less exactly PISA’s RME philosophy coming from Netherlands’ Freudenthal Institute, which emphasizes problem solving and embedding mathematical questions in “real world” situations. So you know that the “direct instruction” variable used there also does not correspond closely to Engelmann’s system but simply falls on the same end of the spectrum as other “garden-variety” direct instruction systems, consistent with the description Stokke gives.

The consistent performance of direct or “fully guided” instruction across many different kinds of tests, and under varying definitions, against indirect, discovery or “minimal guidance” instruction is well-documented, as summarized in the famous article of Kirshner, Sweller and Clark and elsewhere. http://www.cogtech.usc.edu/publications/kirschner_Sweller_Clark.pdf

You seem to feel the need to run interference on this kind of information, reflexively supporting discovery learning, perhaps out of sympathy because of its poor performance at teaching novices under any kind of objective scrutiny. It is helpful that you do so publicly, as the public needs to see that the reason teachers follow unproven methodologies is not because they are stupid, or there is some obscure but overwhelmingly convincing proof that they work, known only to teachers … but because the educationists whose job it is to inform them about best practices deliberately skew such information. I am happy to have “live” examples of this to point to.

That practice used to be pretty effective, because professional educationists had a monopoly on access to teachers and the research literature was largely inaccessible to the general public.

No longer. Today, everyone and his dog can access original research straight from the researcher’s pen, and it is easy to communicate with both teachers and the general public because of the amazing growth of the internet and the networking power of social media. Educationists can no longer operate in isolation from public scrutiny. And it is changing the dynamics of how teachers are connected to the results of research, as the ResearchEd movement testifies by its very existence.

http://www.workingoutwhatworks.com

So … all I’m sayin’ … keep it up.

I’ll revisit this thread, eventually.

Found this lurking in my spam folder.

The behaviorist stuff gives a bit of a hint of how some of these things involve conflated axes; it certainly seemed like a lot of the pushback contemporary for that time was on that specifically (which is weird, since the ultra-behaviorist University of Kansas curriculum didn’t do that well).

You’re starting to sound a little conspiracy-theorist here. Just to clarify, I am a regular classroom teacher, not an “educationalist”. I did, on this post, go and educate myself by reading 500+ pages of original sources, which I then quote at length about.

I was pretty fervent about original sources because other later stuff — including DI websites — seem to have misinformation. I, too, wanted people to inform themselves — that’s why I link to all the actual government papers in question.

I was actually somewhat surprised by the results and fully expected DI to come out a winner (with the caveat being that this was a 40 year old study, and something modern would be more useful) but I instead found a bunch of points mismatched with what others have written. I’m going to assume the best and that people weren’t being blatantly dishonest, but more like there was a game of historical telephone going on where the original message got garbled because people were writing about interpretations of interpretations of interpretations (something I’ve seen before).

You should back up and try opening your own mind a little, here.

Part of what makes all this hard (I might hit this point in a later post) is what Hattie concludes from all his meta-meta-studies that “almost everything works”. The graph is kind of ridiculous — nearly everything has a positive effect if run as an intervention. Some have more positive than others, but it is all tied in with so much context that things nullify each other out. Assigning homework, for instance, has an only marginal positive effect — statistically you could say zero — but I suspect it’s positive in circumstances where students will do their homework (stable families, not necessary for students to have jobs, etc) versus one where it is less likely (more unstable family arrangements which make it harder to get homework done and no habits have been established). In the case of teaching format, I believe we’ve hit adequately here (and you seem to even agree with) that the type of test then used to assess the effectiveness of the format matters. I’m sure school context matters here too. I’ve taught both ends of the spectrum, including University High School (which was in the top 10 of the US News and World Report at the time for public high schools) all the way down to schools with the largest poverty numbers you’re likely to find; while there are some things I can do exactly the same with the same results, the context changes quite a bit what I can do a lesson.

Hi Jason. The confusion over the term “educationalist” may be that there is no universally accepted meaning for the word.

I used to use the term “consultant class” to refer to the heterogeneous grouping of people who, within the world of education, make it their business to inform teachers about how they should be teaching. This would include professors of math, textbook writers who also “consult”, the various travelling gurus and clinicians (guys like Meyer, for example), independent consultancies and educational research outfits and also teachers who hang out a shingle or blog. The downside of that term was that there was no compact and brief way to explain this term to anyone, and nobody knew what I meant until I did.

Getting involved with the ResearchEd movement in UK, I came across their use of the term educationist (or educationalist, a simple variant). As I understand the term it refers to academic side of the theory and practice of teaching; the ResearchEd folks used it as a rubric for essentially the same folks: those people “out there” in the world of education who are seeking to influence how teaching is done, and corresponds almost exactly to my rubric for “consultant class” in this regard — but also includes higher-level bureaucrats in what their education minister M Gove called “the Blob” (for BLOated educational Bureaucracy) a few years back. I freely apply the terms to those within the system (regardless of station) who get involved in such things.

Much of the tone and several things I said in that first comment derive directly from my ludicrous conflation of you with Meyer. We have met online on a few occasions and, for reasons I cannot explain, my mind had you and him blurred into a single person … until after I had posted that comment. If a few things I’d said in earlier conversations seemed strange … that might explain it.

I’ve been reading what I can of your blog posts trying to get clear in my mind where you stand and what your approach is. I regard you as an educationist, but of a different sort altogether from Mr Meyer. At the point I though it was him who wrote this essay, I was genuinely impressed (though my tone probably didn’t convey this very well), as I hadn’t seen much in the way of this kind of careful scholarship on his part prior to this…

I find myself much more in harmony with your thinking on a lot of points than with Mr M, so I’m happy to make the distinction. However, we have enough points of departure, even just on this one post, to have some good back-and-forths, which I hope to do (spread over time).

In your comment here I am unsure of why you are bringing Hattie into this. For one PFT is not a metastudy — perhaps I misunderstand the caveats you’re bringing in, I’m not sure.

For another, as you observe, most of the sponsored interventions in PFT did *not* have positive effect by any of the measures of mathematical skill, cognition and Affective-domain response. So if anything Hattie’s observation only serves as a further indictment of these approaches. I don’t see what, about it, “makes this all hard”. I would think it rather helps to bring the picture into focus.

I see you extensively draw on some of the original sources, whereas I have read extensively in the academic literature summarizing and critiquing. So we are seeing different parts of the whole. Just to illustrate where I think you might be missing part of the picture:

I see no trace here of the Harvard Review volume, for example, that was largely devoted to PFT, or the entire volume of Effective School Practices that compiled articles on the subject and introduced a few new ones. You link to the Glass, House et al critique that was pivotal in scuttling efforts to derive policy implications from the study, but I see no evidence that you have looked at the response response to that critique by Abt associates researchers, or the reply by the U.S. Office of Education. I also don’t recognize any reference to the separate (and quite different) PFT critique by Hodges. You mention the interim report and the Comptroller’s statements about it, but you don’t point out Abt’s qualitatively different assessment of the overall study several years later when their final report came out. You give no evidence of having seen Bereiter and Kurland’s analysis, or that of Becker and Carnine, or Adams or Watkins. Or Linda Meyer’s study on the long-term effects of DI used in PFT, published in the 80’s. Or Haney’s 1977 summary.

You make much of Mathemagentic Activities, although it is given little play in the reports and following scholarship, largely because of the small number (three) of sites at which it was implemented. DI, in contrast, was implemented over 10 sites.

You pay a lot of attention to range-of-response data that obscures what typical or average response at sites for a given intervention might look like. For example, an intervention with a single site having one large positive response and several with large negative response would look, in this out-of-focus picture, identical to one with a single large negative response and several large positive ones: Both would be seen as “having a wide range of responses” from positive to negative, end of story.

This blurring of distinctions through focussing on range of data rather its distribution and center strikes me as a major part of the Glass-House critique.

The effect a single outlier can have in such analysis is particularly important to note in light of the fact that one of the sites listed as DI (Grand Rapids) pulled out from the DI intervention after only a couple of years and adopted a different approach for the remainder of PFT. That site’s scores had a significant negative effect on the DI results (See Becker and Carnine’s analysis) even though it was not using DI, because Abt Associates made the decision to include it in the stats.

In turn, I have not considered many of the points of analysis you raise, and I should find some time to read more about them before we dive into things in earnest; don’t know when that will happen, sorry, but I promise to try to return to this.

Now Jason, after pressing “Post Comment”, to my embarrassment I see I’ve called you “Dan” and just realised I’ve been conflating you and Dan Meyer in my head for a while. I apologize (if you consider that an insult) and you’re welcome (if … the opposite is the case). I suspect a few allusions I’ve made are incorrect. For example I think it was Dan who confessed ignorance of PFT around the beginning of June, not you.

Aside from any such glitches, the rest of my comment stands.

Having reread your post in more detail and done some reading, although you work from different sources than I generally do it is easy enough to compare notes, and there is not that much information in it that is new to me, only a very different frame of reference, and I think we can deal with that. It seems on second reading that the primary purpose of this post is to run interference on the success of DI in PFT, so I suppose I should not be surprised on some of the obscurities you placed great weight upon and the rather prominent aspects you left unmentioned or underemphasized.

I continue to take exception to your characterization of direct instruction today as consisting of “lectures and notes”. I doubt you could find a direct instruction K-3 classroom anywhere in the continent for which this is an adequate description of the instruction. It is clear what you are trying to do here. I doubt you think that direct instruction advocates today want every classroom to look like a first-year calculus class … but you find it helpful to use language that implies that this is precisely the case. This is dishonest.

Yes, DISTAR instruction style is uncommon, in direct instruction classes today; you’ll find a more helpful description of what direct instruction is taken to encompass in Stokke’s CD Howe report,

Click to access commentary_427.pdf

In particular the strong emphasis on behaviourist methods is uncommon and one may regard it as peripheral to what makes this a “direct instruction” system in the same way that wearing school uniforms in a discovery education class does not make uniforms an aspect that falls under “discovery education”.

Even so I have been struck by the strong resemblance between Engelmann’s style of interaction in DI and that of trained instructors using the JUMP Math system — which, if you haven’t read about, there is a helpful NYT piece about it here:

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/04/18/a-better-way-to-teach-math/

As you can see, JUMP Math seems to consistently produce remarkably strong performance results in the same way as DI has done. I asked Mighton a couple of years ago if he had ever heard of Engelmann’s DI system. He arrived at his system entirely independently (but not through a completely dissimilar process).

The comparison in PFT is only one of many ways of parsing “direct” versus “indirect” instruction. There are many different ways to do so and many comparisons have been done, only a few involving Engelmann’s particular form of DI. I believe, for example, you have written about the PCAP 2010 contextual data. Remarkably consistently, direct instruction approaches in K-12 education perform significantly better than indirect independently of who does the parsing and what specific descriptors are use.

Hattie, whom you mention, the king of educational metadata, points this out. I was having a debate a year ago with an educationist in Alberta who insisted that Engelmann’s approach to DI should not be taken as a definition of the system (of which he said some elements were good, though he was a discovery advocate himself). I asked him how he would define DI, then. He said that he was an admirer of Hattie and felt that his book gives the best definition of direct instruction. I looked up the definition in the book. Hattie’s definition is a direct quote from Engelmann’s writing on the subject, and Hattie credits him for it in the book. For his meta-analysis on direct instruction, Hattie lumps DISTAR together with many other forms of direct instruction.

Seems to me that the distinction in question is a red herring. It appears Hattie (and also, inadvertently, this Alberta fellow) would support that. Direct is direct, whatever other bells and whistles one attaches to it. Indirect is indirect. They are both broad categories and encompass many “named” specific methodologies.

I continue to take exception to your characterization of direct instruction today as consisting of “lectures and notes”.

Fair enough. But note that a lot of people (including practitioners who I have actually conversations with who argued about it) think of it that way. This relates to your point later…

For his meta-analysis on direct instruction, Hattie lumps DISTAR together with many other forms of direct instruction.

Ayep. My comment earlier was getting at my frustration with lumping. It sounds like you might be frustrated too; that someone who claims their students want the material told to them / examples done / practice done would be categorized wtih DISTAR. Do realize they are pulling out the same types of studies you are to justify what they are doing.

Fair enough. But note that a lot of people (including practitioners who I have actually conversations with who argued about it) think of it that way. This relates to your point later…

I don’t know of anyone who advocates lecturing and note-taking in K-3 classes.

I do know of a number of detractors of DI approaches who harp on a recent study of university classes comparing lectures against project-based learning, and who (in complete ignorance, apparently, of the expert reversal effect) believe that this informs the debate about teaching Primary-Grade mathematics (which is what PFT was about). It is not a suitable rubric since essentially nobody teaches or advocates teaching K-3 like that. The only people I see who try to make the case that this is what DI consists of are those who seem to believe it helps make a case against it.

I’d rather deal with what’s ACTUALLY on the table, not straw men.

In particular you won’t find the word “lecture” in Stokke’s CD Howe report, which seems to have sparked the latest round of debates on this subject.

I realize the lecture reference was a bit glib, so I cut it out.

Follow Through gets referenced all the time for not just K-3, so I was speaking in general. I possibly should’ve had a point (f.) — any conclusions really only apply to early education, and it’s hard to extrapolate (and this goes both ways, so for instance if someone wanted to run with the mathemagnetic activity thing they’d have to keep that in mind).

I don’t go so far as to say “any conclusions really only apply to early education” [K-3 that is, not preschool]. However it is quite correct to say that to properly broaden the application one has to be cautious about what this study might imply in other contexts. I believe the expert reversal effect (for one) is a critical barrier to applying what the findings here directly to adult students at university and even to high school education. The game is different when students come into a class with a strong foundation of relevant domain knowledge already in place. Interestingly, I have come across numerous blogs in which studies about pedagogies in university classes are used to draw inferences about early-years education, which is problematic in much the same way.

I’ll add to this caveat, because it’s important to understand the context of research: PFT was an intervention for SES-disadvantaged students. As a cohort this group had a baseline performance around the 20th percentile. This was not a study of average-opportunity students (though I think it’s fair to say we have no reason to believe they are not of average intrinsic ability — these are “ordinary kids in unfortunate circumstances”).

I find it a bit remarkable that the point about SES is not often raised when people object to follow through. It is an important consideration. It certainly does not mean we can’t draw inferences about other populations, but it does mean that this should be done with cautionary language, or (as we do when we hold this up alongside other studies involving direct versus discovery education) in the presence of multiple lines of evidence that broaden the context of the conclusions.

The first thing is to come to the best conclusions we can about PFT as it was performed and in the precise context in which it happened (and you have contributed to that in this post). From there we can talk about other contexts in which some principles gleaned are likely to apply.

Hi Jason, one of the main things I needed to do before we could talk at length here was to get up to snuff on the Mathemagenic Activities (MAP) model, which I had heretofore ignored because it was not a major model (because of the small number of sites — only 3 instead of the required 5) and it is not included in the longitudinal data because it was only implemented for one cohort.

My reading of the PFT description of MAP is that, while its theoretical framework is Piagetian and social constructivist in the tradition of Vygotsky, in practical terms it is

(i) a highly programmed system of instruction

(ii) based on incremental learning

(iii) with a strong, content-oriented (as opposed to process-oriented) design.

From this description alone it is pretty hard to reconcile with, as you say, the “modern ‘discovery’ curriculum”. Each of these three aspects is at odds, for example, with the basic design of materials by (for example) Jo Boaler and Canada’s discovery-ed guru Marian Small. Nevertheless, the point is there that, aside from those three implementational elements, there is a philosophical connection under the surface.

That was my view until I started reading the work of Rothkopf, the developer of Mathemagenic Activities as an educational theory in which the Piagetian element is less evident and that he appears to draw more heavily on Vygotsky for the concept of zone of proximal development (which is not strictly a “constructivist” idea) than for anything pertaining to social constructivism. Unfortunately, the writings I could find by Rothkopf were highly specific and didn’t lay out the theory very well, though they hinted at a behaviorist framework.

Then I found this piece: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED114279.pdf

written during the time PFT was still happening, which lays out both the theoretical and the implementational sides of Mathemagenic Behavior (and Activities) — unfortunately only going into detail for Science Education, but it is not hard to triangulate to Math Education.

I’ll leave it to you to decide whether you concur with my assessment. I find little in the theory besides sideways references to ideas often attributed to Vygotsky (I’m not sure about Piaget; in any case neither is cited) and that it clearly falls into child-centered instruction (more on this in a sec) that would suggest a similitude to the popular current educational notions of “discovery learning”.

As far as being child-centered, I find elements of the program that seem based on the same ideas as self-instruction based on mastery learning. In fact, proponents of MAP actually write about this connection. The idea is that a sequence of questions in small increments lead to mastery of content, whether sequenced through reading materials and workbooks or exploratory questions given by teachers. I’m not sure that qualifies as “child-centered”. I spent a week in June evaluating a “student-centered” remedial system in use at Memorial university to remediate students who are deficient in their math background. It consists largely of a series of workbooks they work through. Teachers are present to provide help, direction and testing. Although it is student-centered in a strict sense that most instruction takes place while the student works on their own through the course materials, it is also Direct Instruction in the sense that material is directly given to the student and they are to learn what they are taught. I’m not “accusing” MAP of being a workbook system — but I do get the impression that it has something of the same flavour, in which the teacher plays “workbook” and the instructional tasks are more discovery-oriented.

In fact, I think in the main the theory falls more closely in line with behaviorist theory and practice, with the emphasis on strict, goal-oriented learning, careful programming of instruction and question-and-answer instruction based on eliciting particular desired behaviors in students. I could not have gleaned this from the PFT description, although if you look there are plenty of clues there. I suspect the description in the Abt materials derives from a desire to fit the model more neatly into its classification.

The same can be said for the description of Mathemagenic Activities in the OE materials. Again, it appears that the focus is on highlighting how MAP fits into one of the three categories. Also, I disagree, after reading in more detail about MAP, with the Abt judgement placing the system into the “medium degree of structure”. Judging from thes external descriptions I have found of the system it should probably be considered to have a high degree of structure.

A couple of other things stand out relative to MAP versus DI. First, the DI FT sites tended to have slightly lower SES and slightly higher second-language and proportion of minority-group scores relative to both the local and global comparison NFT sites, whereas MAP had the opposite — higher SES and lower proportion of English as a second language and minority group students. Make from that what you will.

Further, as you noted MAP, as an available curriculum, appears to have disappeared off the, er, map, about the time PFT came to a close; whereas DI has continued on and is still under development (though strenuously ignored by the Educational Community):

Further, several follow-up studies to PFT are available on the long-term educational benefits of DI instruction through high school and into college (including one well-known hostile “study” associated with one of the other PFT sponsors that suggests DI leads kids to become felons later in life).

If you’re looking for, as you say ‘what most people would consider closest to a modern “discovery” curriculum.’, how about taking a look at the High/Scope Cognitively-Oriented Curriculum? That is where my vote would be. In fact, reading its philosophy documents alongside Jo Boaler’s writings, I was under the impression for some time that her work is a direct descendant of High/Scope. I confess, however, that I have never found direct evidence of this; I suppose they are independently arrived at.

High/Scope is still available and under development, though it seems to me that today it focusses more intensely on early education. A couple of other models also strike me as at least as close to contemporary “discovery” learning as MAP: TEEM, Responsive Education, and the Bank Street Model. But I imagine you’ll disagree with this assessment.

Direct Instruction (the general kind) more effective than indirect methods with first graders http://edexcellence.net/articles/the-effectiveness-of-instructional-practices-for-first-grade-math